HIV prevalence and its association with cervical cancer risk in southern Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Eugene-Jamot Ndebia 1, Gabriel Tchuente Kamsu 1

1 Department of Human Biology, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Walter Sisulu University, Nelson Mandela Drive, Mthatha, South Africa

*Correspondence: Eugene-Jamot Ndebia. Email: endebia@wsu.ac.za

Received: 27-02-2025

Accepted: 24-04-2025

DOI: 10.24875/AIDSRev.25000003

Available online: 26-06-2025

AIDS Rev. 2025;27(3):71-78

Abstract

Southern Africa is characterized by exceptionally high rates of HIV prevalence and incidence of cervical cancer, exceeding those observed in other regions of the continent. This situation highlights the urgent need for targeted and coordinated public health action. In this context, this review aims to clarify the links between these two diseases, to understand their interaction better, and to guide prevention and treatment strategies adapted to this high-risk region. This study, conducted according to the PRISMA 2020 guidelines, explored the impact of HIV on the risk of cervical cancer and the prevalence of HIV among cervical cancer patients in southern Africa. Eighteen original studies, covering six countries in the southern Africa region and published between 2003 and 2022, were included. The prevalence of HIV in patients with cervical cancer was 5.30% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 4.21-6.67; and p = 0.001). In addition, the analysis revealed a significant association between HIV infection and an increased risk of cervical cancer, with an overall odds ratio of 2.29 (95% CI: 1.62-3.23; p = 0.001). Tests for publication bias showed no significant bias, and trim-and-fill analysis did not reveal any missing studies. In conclusion, this study highlights a high prevalence of HIV among cervical cancer patients in southern Africa, with a strong association between HIV infection and an increased risk of this form of cancer. These findings underline the importance of integrated prevention strategies, including human papillomavirus vaccination, cervical cancer screening, and improved access to antiretrovirals, to reduce the combined burden of HIV and cervical cancer in this high-risk region.

Contents

Introduction

HIV infection and cervical cancer are major public health challenges worldwide, particularly in regions where HIV is endemic1,2. Cervical cancer, one of the most common cancers among women, causes significant loss of life, especially in developing countries where access to preventive care and screening remains limited3. According to the World Health Organization4, approximately 660,000 new cases of cervical cancer are diagnosed each year, resulting in over 350,000 deaths. Southern Africa, mainly affected by this disease, experiences a high mortality rate due to the lack of large-scale screening programs and the high prevalence of co-infections, which are major risk factors for this type of cancer5–7.

At the same time, the region faces an alarming prevalence of HIV, with approximately 20.8 million people living with the virus, accounting for 53% of the global HIV-infected population8. The coexistence of these two severe diseases, characterized by higher HIV prevalence and cervical cancer incidence rates than in other regions of the continent, calls for targeted and coordinated actions9.

In response to this dual burden of morbidity, exploring the complex links between these two diseases is essential to effectively guide prevention and treatment strategies. While many systematic reviews have examined the role of human papillomavirus (HPV) and the relationship between the Pap smear and cervical cancer, controversies persist regarding the link between HIV infection and the risk of cervical cancer. Some studies conclude that there is no link10,11, while others suggest an association between the two diseases12,13. However, no meta-analysis specific to the southern African subregion has been conducted to date, although such an analysis is essential to address the existing gaps in understanding this link.

This systematic review is justified by the lack of consolidated data on the combined prevalence of HIV and cervical cancer, which limits the effectiveness of public health policies in this high-risk area. By rigorously analyzing the available data, this review aims to clarify the links between these two diseases, assess the impact of the present health programs, and provide evidence-based recommendations. These recommendations will improve the management of this co-epidemic and strengthen integrated interventions to address both HIV and cervical cancer simultaneously. Finally, this analysis will offer a valuable opportunity to raise awareness among local and subregional health authorities about the importance of developing coherent and coordinated strategies to address this major public health issue.

Materials and methods

This study followed the PRISMA 2020 recommendations, ensuring a transparent, reproducible, structured approach to systematic reviews and meta-analyses14. The studies included in this review were original research on the female population living in southern Africa, assessing the impact of HIV on the risk of cervical cancer and the prevalence of HIV among cervical cancer patients. These studies had to meet a number of criteria: they had to have received ethical approval, take account of confounding factors, and be published in peer-reviewed scientific journals. Studies of populations outside southern Africa, non-peer-reviewed sources, and editorials and letters were excluded.

The primary exposure of interest was HIV status, with cervical cancer risk as the outcome criterion. The secondary exposure was HIV prevalence among cervical cancer patients. An exhaustive search was conducted in Scopus, PubMed/Medline, Web of Science, Google Scholar, and African Journal Online databases, using keywords associated with HIV and southern Africa. The identified studies were first exported to EndNote, where duplicates were removed, and then to Rayyan software to better organize the selection and review process15.

Data extraction, including study characteristics and participant details (age, sample size, HIV status), was done by G.T.K. and E.J.N. The main statistical parameters, such as odds ratios and relative risks, were collected. Study quality was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa scale16, focusing on methodological rigor and validity. Data synthesis involved organizing and summarizing the results, with narrative synthesis and statistical analysis, carried out using STATA 18.017. The inverse variance method was used to estimate the effects, applying a random effects model and assessing heterogeneity using the I2 statistic18. A subgroup analysis was carried out to explore the role of HIV in the risk of cervical cancer, as well as the prevalence of HIV among cancer patients in this subgroup. Publication bias was assessed visually using a funnel plot, and Egger’s regression test was applied to assess skewness, with a p < 0.10 indicative of bias19,20.

Results

Characteristics of included studies

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the studies included in this meta-analysis. After searching various databases, 18 original studies meeting our inclusion criteria were included10–13,21–34. These studies, conducted in the South African sub-region (Fig. 1), came from South Africa (10 studies), Mozambique (2 studies) and Eswatini (2 studies). One study was identified in Botswana, Malawi, and Namibia. The patients, all adults, were considered to have cervical cancer following examination of cervical swabs for cytological review and cervical biopsies for histopathological review in some cases and by visual inspection with acetic acid examination, confirmed by colposcopy for others.

Table 1. Studies characteristics

| Author’s (date) | Country | Study population | Different HIV parameters evaluate | Period of collect | Cervical cancer diagnostic methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Van Aardt et al. (2015)21 | South Africa | Adults (≥ 18 years) | HIV Status | 2003-2004, and 2008 until 2011 | Tissue biopsies for histological confirmation |

| Naucler et al. (2011)10 | Mozambique | Adults (≥ 18 years) | HIV Status | May 2002- November 2006 | Cervical swabs for cytological review and cervical biopsies for histopathology review for suspected patients |

| Friebel-Klingner et al. (2021)22 | Botswana | Adults (≥ 18 years) | HIV status; CD4 counts; ART treatment | January 2015 and March 2020 | Diagnosed and confirmed with cervical cancer in their medical records |

| Gerstl et al. (2022)23 | Malawi | Adults (≥ 18 years) | HIV status | 2019 | Diagnosed and confirmed with cervical cancer in their medical records |

| Rostad et al. (2003)24 | Mozambique | Adults (≥ 18 years) | Sexually transmitted diseases | Diagnosed and confirmed with cervical cancer in their medical records | |

| Eiman (2020)25 | Namibia | Adults (≥ 18 years) | HIV status | January 01, 2016-June 30, 2018 | Cervical swabs for cytological review; diagnosis, and confirmed with cervical cancer in their medical records |

| Jolly et al. (2017)26 | Swaziland (Eswatini) | Adults (≥ 18 years) | HIV status | Cervical swabs for cytological review and confirmed using VIA methods | |

| Khumalo et al. (2024)27 | Swaziland (Eswatini) | Adults (≥ 25 years) | HIV status | October-December 2021 | Diagnosed and confirmed with cervical cancer in their medical records |

| Dryden-Peterson et al. (2016)28 | Botswana | Adults (≥ 18 years) | HIV status; CD4 counts; Initiated ART before cancer diagnosis | 2010-2015 | Diagnosed and confirmed with cervical cancer in their medical records |

| Firnhaber et al. (2013)29 | South Africa | Adults (≥ 18 years) | HIV status; CD4 counts | Cervical swabs for cytological review using VIA methods and confirmed using colposcopy | |

| Dhokotera et al. (2022)12 | South Africa | Adults (≥ 15 years) | HIV status | 2004-2014 | Diagnosed and confirmed with cervical cancer in their medical records |

| Suleman and Botha (2021)30 | South Africa | Adults (≥ 18 years) | HIV status; CD4 counts; ART treatment; viral load | January 2014- December 2018 | Diagnosed and confirmed with cervical cancer in their medical records using colposcopy |

| Chattopadhyay et al. (2015)11 | South Africa | Adults (≥ 18 years) | HIV status | 2009 | Cervical swabs for cytological review and confirmed with cervical cancer in their medical records |

| Singini et al. (2022)13 | South Africa | Adults (≥ 18 years) | HIV status | 1995 and 2016 | Cervical swabs for cytological review and cervical biopsies for histopathology review for suspected patients |

| Turdo et al. (2022)31 | South Africa | Adults (≥ 18 years) | HIV status; CD4 counts; HIV RNA viral load; Initiated ART before cancer diagnosis | January 2011 and July 2020 | Cervical swabs for cytological review and cervical biopsies for histopathology review for suspected patients |

| Moodley et al. (2006)32 | South Africa | Adults (≥ 18 years) | HIV status | January 1998 to December 2001 | Histologically confirmed invasive cervical cancer |

| Singini et al. (2021)33 | South Africa | Adults (≥ 18 years) | HIV status | Between 1995 and 2016 | Histologically confirmed invasive cervical cancer |

| Moodley et al. (2009)34 | South Africa | Adults (≥ 18 years) | HIV status; CD4 count | Cervical swabs for cytological review and colposcopy examination | |

|

* Absence of data collection period. VIA: visual inspection with acetic acid; ART: antiretroviral therapy. |

Figure 1. Map of southern Africa.

Prevalence of HIV infection in a southern African population with cervical cancer

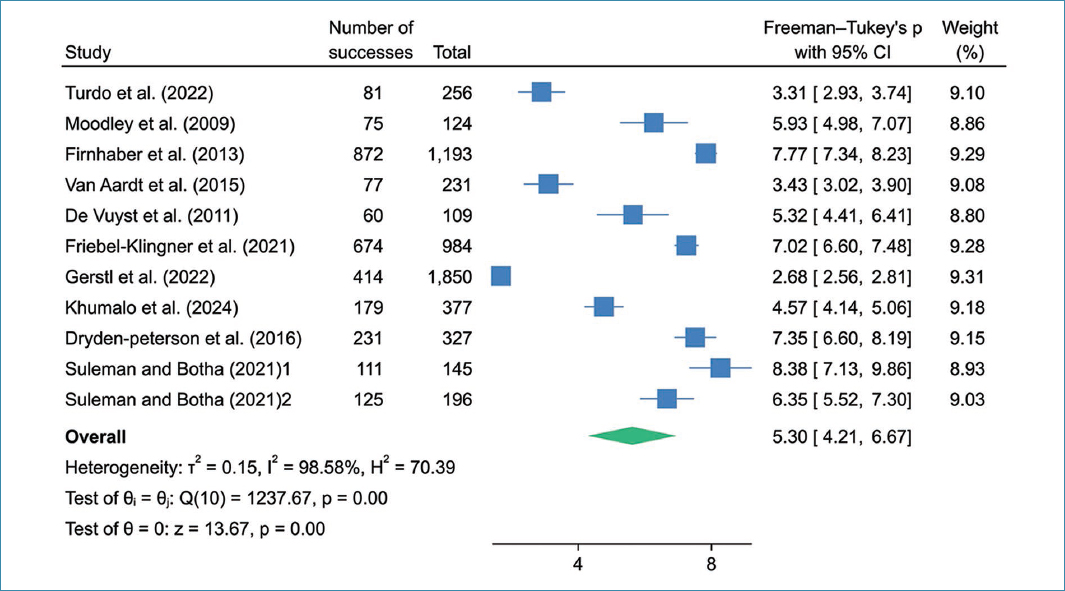

Figure 2 shows the prevalence of HIV infection in cervical cancer patients in southern Africa. The pooled prevalence of HIV infection in cervical cancer patients in southern Africa with the random-effects model of 11 studies was 5.30% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 4.21-6.67) with significant heterogeneity I2 = 98.58%, p = 0.0001.

Figure 2. Pooled prevalence of HIV infection among cervical cancer women in southern Africa.

Influence of HIV on cervical cancer risk in southern Africa

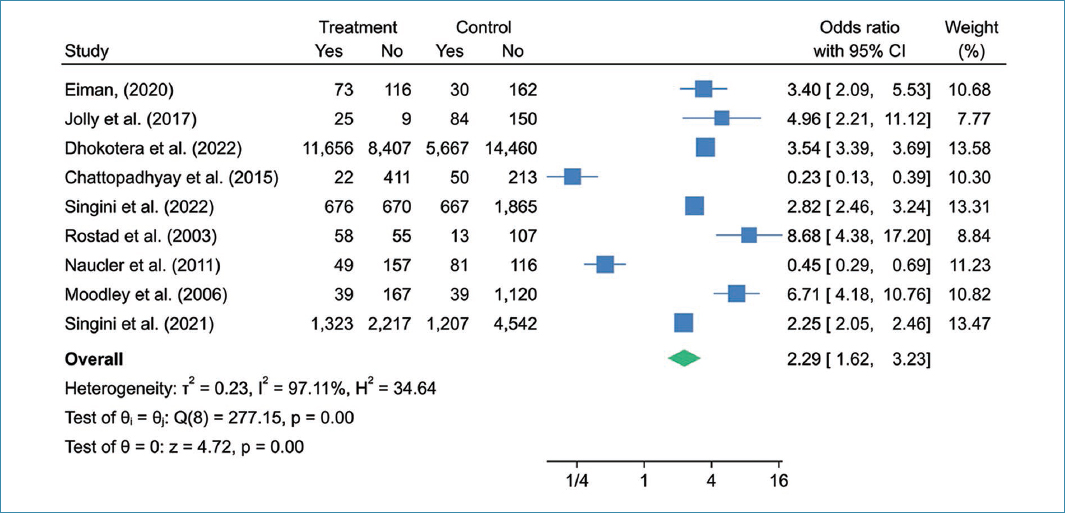

The forest diagram shown in figure 3 illustrates the association between HIV infection and cervical cancer in southern Africa. Analysis of this figure reveals a pooled odds ratio of 2.29 (95% CI: 1.62-3.23, p = 0.001) and a substantial degree of heterogeneity (I2 = 97.11%). These results strongly suggest a significant association between HIV infection and oesophageal cancer.

Figure 3. Forest diagram of association between HIV infection and cervical cancer among women in southern Africa.

Assessing the risk of publication bias and the effects of small studies

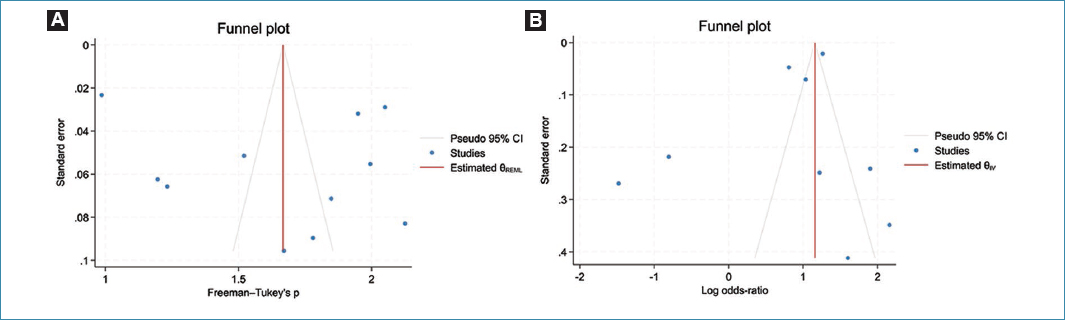

Figure 4 shows the funnel plot for the prevalence of HIV infection, used to assess the possibility of publication bias. Visual inspection of figures 4A and B revealed an asymmetric distribution of study results. However, Egger’s tests yielded p = 0.5823 and 0.8729 for figure 4A and B, respectively, suggesting the absence of publication bias. In addition, the Trim-and-Fill analysis and the corrected funnel plot showed no missing studies in the two meta-analyses.

Figure 4. Funnel plots assessing the potential for publication bias. A: funnel plots for the prevalence of HIV infections among women with cervical cancer; B: funnel plots based on the association between HIV infections and risk of cervical cancer.

Discussion

The results of this meta-analysis offer a valuable perspective on the health situation in the southern African sub-region, where HIV infection and cervical cancer coexist at worrying rates6,7. The inclusion of a majority of studies from six countries, namely, South Africa (10 studies), Mozambique (2 studies), Eswatini (2 studies), as well as an additional study from Botswana, Malawi, and Namibia, highlights the geographical diversity and local specificities of the data collected. These findings are of particular importance given the unique health challenges faced by these countries, where HIV prevalence and the burden of cervical cancer are exceptionally high.

The analysis also revealed an estimated prevalence of HIV infection among cervical cancer patients in southern Africa of 5.30% (95% CI: 4.21-6.67). Although this prevalence is lower than that of other data, it remains consistent with rates observed in studies of co-infection in Ethiopia35. These results corroborate the findings of previous studies suggesting that HIV infection may exacerbate vulnerability to cervical cancer due to the immunosuppression associated with HIV, thereby favoring infection with HPV, the main etiological factor in this pathology36,37.

Concerning the influence of HIV on the risk of developing cervical cancer, the overall odds ratio of 2.29 (95% CI: 1.62-3.23, p = 0.001) observed in this study supports a significant association between HIV infection and increased risk of cervical cancer. This result is consistent with the work of Geremew et al.38 in Ethiopia, who reported an odds ratio of 2.86 (95% CI: 1.79-4.58). This association may be explained by several mechanisms linked to HIV-induced immunosuppression39, including the weakening of the immune system, notably CD4+ cells, thereby reducing the body’s ability to control persistent infections such as that caused by HPV, the leading risk factor for cervical cancer40. In people living with HIV, HPV infection may persist longer, progressing to pre-cancerous or cancerous lesions41. In addition, non-adherence to antiretroviral treatment, which compromises treatment efficacy and worsens immunosuppression, further increases the risk of cervical cancer. This contrasts with the work of Kamsu-Tchuente and Ndebia17, who reported no association between HIV and esophageal cancer in the same geographical area.

The significant heterogeneity (I2 = 98.58%; p = 0.0001) observed in this analysis could result from the variability of methodologies between studies and differences in the populations studied. HIV prevalence and patient selection criteria vary from country to country, which may explain this high level of heterogeneity. However, this heterogeneity (I2 = 97,11%; p = 0.001) also highlights the fact that local contextual factors, such as dietary habits, level of education, socioeconomic status, access to care, and screening strategies in each country may modulate the impact of HIV on cervical cancer risk. In addition, the absence of missing studies, as shown by the Trim-and-Fill analysis, reinforces the robustness of the results, minimizing concerns about publication bias and systematic bias.

These results, which confirm the link between HIV and cervical cancer, also underline the importance of integrated prevention strategies. The coexistence of these two diseases in a high-risk region calls for appropriate public health policies, including more accessible prevention and screening measures, particularly for women living with HIV. Such an approach could include intensified HPV vaccination programs, regular cervical cancer screening, and improved access to antiretroviral treatment, which would play a key role in reducing the combined burden of HIV and cervical cancer in this region.

Conclusion

This study highlights a high prevalence (5.30% [95% CI: 4.21-6.67]) of HIV among cervical cancer patients in southern Africa, with a strong association (2.29 [95% CI: 1.62-3.23) between HIV infection and an increased risk of this form of cancer. These findings underline the importance of integrated prevention strategies, including HPV vaccination, cervical cancer screening, and improved access to antiretrovirals, to reduce the combined burden of HIV and cervical cancer in this high-risk region.

Funding

This study was supported by the Chemical Industries Education and Training Authority funding attributed to Prof. E.J. Ndebia.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript.

Ethical considerations

Protection of humans and animals. The authors declare that no experiments involving humans or animals were conducted for this research.

Confidentiality, informed consent, and ethical approval. The study does not involve patient personal data nor requires ethical approval. The SAGER guidelines do not apply.

Declaration on the use of artificial intelligence. The authors declare that no generative artificial intelligence was used in the writing of this manuscript.

References

1. Vermund SH, Sheldon EK, Sidat M. Southern Africa:the highest priority region for HIV prevention and care interventions. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2015;12:191-5.

2. Singh D, Vignat J, Lorenzoni V, Eslahi M, Ginsburg O, Lauby-Secretan B, et al. Global estimates of incidence and mortality of cervical cancer in 2020:a baseline analysis of the WHO global cervical cancer elimination initiative. Lancet Glob Health. 2023;11:197-206.

3. Hull R, Mbele M, Makhafola T, Hicks C, Wang SM, Reis RM, et al. Cervical cancer in low and middle-income countries. Oncol Lett. 2020;20:2058-74.

4. World Health Organization (WHO). Cervical Cancer. World Health Organization. Geneva, Switzerland:2024. Available from:https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cervical-cancer

5. Chirenje ZM, Rusakaniko S, Kirumbi L, Ngwalle EW, Makuta-Tlebere P, Kaggwa S, et al. Situation analysis for cervical cancer diagnosis and treatment in east, central and southern African countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2001;79:127-32.

6. Sitas F, Parkin M, Chirenje Z, Stein L, Mqoqi N, Wabinga H. Cancers. In:Jamison DT, Feachem RG, Makgoba MW, Bos ER, Baingana FK, Hofman KJ, et al., . Disease and Mortality in Sub-Saharan Africa. 2nd ed., Ch. 20. Washington, DC:The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development The World Bank;2006. Available from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/nbk2293

7. Dlamini Z, Molefi T, Khanyile R, Mkhabele M, Damane B, Kokoua A, et al. From incidence to intervention:a comprehensive look at breast cancer in South Africa. Oncol Ther. 2024;12:1-11.

8. UNAIDS. Global HIV and AIDS Statistics – Fact Sheet. UNAIDS;2024a. Available from:https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet

9. UNAIDS. Eastern and Southern Africa:Regional Profile. UNAIDS;2024b. Available from:https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media-asset/2024-unaids-global-aids-update-eastern-southern-africa-en.pdf

10. Naucler P, Mabota Da Costa F, Da Costa JL, Ljungberg O, Bugalho A, Dillner J. Human papillomavirus type-specific risk of cervical cancer in a population with high human immunodeficiency virus prevalence:case-control study. J Gen Virol. 2011;92:2784-91.

11. Chattopadhyay K, Williamson AL, Hazra A, Dandara C. The combined risks of reduced or increased function variants in cell death pathway genes differentially influence cervical cancer risk and herpes simplex virus type 2 infection among black Africans and the mixed ancestry population of South Africa. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:680.

12. Dhokotera T, Bohlius J, Spoerri A, Egger M, Ncayiyana J, Olago V, et al. The burden of cancers associated with HIV in the South African public health sector, 2004-2014:a record linkage study. Infect Agents Cancer. 2019;14:12.

13. Singini MG, Singh E, Bradshaw D, Chen WC, Motlhale M, Kamiza AB, et al. HPV types 16/18 L1 E6 and E7 proteins seropositivity and cervical cancer risk in HIV-positive and HIV-negative black South African women. Infect Agents Cancer. 2022;17:14.

14. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement:an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:71.

15. Kamsu GT, Ndebia EJ. Socioeconomic determinants of esophageal cancer incidence in the East African corridor:a systematic review with meta-analysis. Int J Med Arts. 2024;6:4374-85.

16. Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25:603-5.

17. Kamsu-Tchuente G, Ndebia EJ. HIV infection and esophageal cancer in Sub-Saharan Africa:a comprehensive meta-analysis. AIDS Rev. 2024;26:15-22.

18. DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177-88.

19. Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629-34.

20. Kamsu GT, Ndebia EJ. Uncovering risks associated with smoking types and intensities in esophageal cancer within high-prevalence regions in Africa:a comprehensive meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2024;33:874-83.

21. Van Aardt MC, Dreyer G, Pienaar HF, Karlsen F, Hovland S, Richter KL, et al. Unique human papillomavirus-type distribution in South African women with invasive cervical cancer and the effect of human immunodeficiency virus infection. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2015;25:919-25.

22. Friebel-Klingner TM, Luckett R, Bazzett-Matabele L, Ralefala TB, Monare B, Nassali MN, et al. Clinical and sociodemographic factors associated with late stage cervical cancer diagnosis in Botswana. BMC Womens Health. 2021;21:267.

23. Gerstl S, Lee L, Nesbitt RC, Mambula C, Sugianto H, Phiri T, et al. Cervical cancer screening coverage and its related knowledge in southern Malawi. BMC Public Health. 2022;22:295.

24. Rostad B, Schei B, Da Costa F. Risk factors for cervical cancer in Mozambican women. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003;80:63-5.

25. Eiman E. Assessment of Risk Factors Associated with Cervical Cancer Amongst Women Attending the Oncology Center and Health Facilities in Windhoek, Thomas Region. Master of Science Thesis in Applied Field Epidemiology. Namibia:University of Namibia;2020.

26. Jolly PE, Mthethwa-Hleta S, Padilla LA, Pettis J, Winston S, Akinyemiju TF, et al. Screening, prevalence, and risk factors for cervical lesions among HIV positive and HIV negative women in Swaziland. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:218.

27. Khumalo PG, Carey M, Mackenzie L, Sanson-Fisher R. Cervical cancer screening knowledge and associated factors among Eswatini women:a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2024;19:0300763.

28. Dryden-Peterson S, Bvochora-Nsingo M, Suneja G, Efstathiou JA, Grover S, Chiyapo S, et al. HIV infection and survival among women with cervical cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:3749-57.

29. Firnhaber C, Mayisela N, Mao L, Williams S, Swarts A, Faesen M, et al. Validation of cervical cancer screening methods in HIV positive women from johannesburg South Africa. PLoS One. 2013;8:53494.

30. Suleman R, Botha MH. A retrospective study comparing the efficiency of recurrent LSIL cytology to high-grade cytology as predictors of high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia or worse (CIN2+). S Afr J Gynaecol Oncol. 2021;13:18-25.

31. Turdo YQ, Ruffieux Y, Boshomane TM, Mouton H, Taghavi K, Haas AD, et al. Cancer treatment and survival among cervical cancer patients living with or without HIV in South Africa. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2022;43:101069.

32. Moodley JR, Hoffman M, Carrara H, Allan BR, Cooper DD, Rosenberg L, et al. HIV and pre-neoplastic and neoplastic lesions of the cervix in South Africa:a case-control study. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:135.

33. Singini MG, Sitas F, Bradshaw D, Chen WC, Motlhale M, Kamiza AB, et al. Ranking lifestyle risk factors for cervical cancer among Black women:a case-control study from Johannesburg, South Africa. PLoS One. 2021;16:0260319.

34. Moodley M, Lindeque G, Connolly C. Human papillomavirus (HPV)-type distribution in relation to oral contraceptive use in women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, Durban, South Africa. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2010;31:278-83.

35. Mekonnen DB. Cervical cancer screening uptake and associated factors among HIV-positive women in Ethiopia:a systematic review and meta-analysis. Adv Prev Med. 2020;2020:7071925.

36. Kangethe JM, Gichuhi S, Odari E, Pintye J, Mutai K, Abdullahi L, et al. Confronting the human papillomavirus–HIV intersection:cervical cytology implications for Kenyan women living with HIV. S Afr J HIV Med. 2023;24:1508.

37. Denny LA, Franceschi S, De SanjoséS, Heard I, Moscicki AB, Palefsky J. Human papillomavirus, human immunodeficiency virus and immunosuppression. Vaccine. 2012;30 Suppl 5:F168-74.

38. Geremew H, Tesfa H, Mengstie MA, Gashu C, Kassa Y, Negash A, et al. The association between HIV infection and precancerous cervical lesions. A systematic review and meta-analysis of case-control studies. Health Sci Rep. 2023;6:1485.

39. Swase TD, Fasogbon IV, Eseoghene IJ, Etukudo EM, Mbina SA, Joan C, et al. The impact of HPV/HIV co-infection on immunosuppression, HPV genotype, and cervical cancer biomarkers. BMC Cancer. 2025;25:202.

40. Abraham AG, D'Souza G, Jing Y, Gange SJ, Sterling TR, Silverberg MJ, et al. Invasive cervical cancer risk among HIV-infected women:a North American multicohort collaboration prospective study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;62:405-13.

41. Liu G, Sharma M, Tan N, Barnabas RV. HIV-positive women have higher risk of human papillomavirus infection, precancerous lesions, and cervical cancer. AIDS. 2018;32:795-808.