Human ecology: a bridge between medical ethics and the 2030 Agenda

Luisa González 1, Vicente Soriano 2

1 Department of Anesthesiology, Puerta de Hierro University Hospital. Madrid, Spain; 2 UNIR Health Sciences School and Medical Center, Universidad Internacional de La Rioja, Madrid, Spain

*Correspondence: Luisa González. Email: steinglez@gmail.com

Received: 22-07-2025

Accepted: 10-09-2025

DOI: 10.24875/AIDSRev.M25000085

Available online: 16-10-2025

AIDS Rev. 2025;27(2):55-62

Abstract

The United Nations (UN) 2030 agenda is a developing program that aligns all human activities with the goodness and fullness of our planet. Sustainable development goals are grouped into categories, including planet, people, and partnership. Whereas ecology refers to caring for all elements of creation, human ecology points out that man specifically is part of it. It is at this point that medical ethics intersects with ecology. The responsibility of humans for the environment, living beings (animals and plants), and other men is needed for driving all creation to flourishing. Disregarding any of these elements would compromise the whole fulfillment by creatures on Earth, given their close interrelationship. Human abuse, instrumentalization, or exploitation of creatures–including one’s own human being–would ultimately destroy our planet. Rather than empowering us with no limits, we should view creation as a gift and we, humans, as caregivers. Given the transformative power of human actions, concerns and regulations are required. This is why medical ethics should guide biotechnological advances, and the cautionary principle should prevail in human research. In this regard, ecology should be understood as the ethics of care. In a pyramidal way, caring should begin with human beings, followed by animals and plants, and finally consider the habitat we live in. In medicine, promoting “one health” underscores the need to expand caring beyond our own species, attending to the consequences of our actions on the environment and other living beings on our planet. The recent experience with the COVID-19 pandemic highlights the risk of zoonoses and the need for confronting human diseases globally.

Contents

Introduction

There is a close relationship between ecology and bioethics. Ecology describes the life of ecosystems, and bioethics the moral conduct of man. Both the external nature and the person have a created value, and they are subjects of rights and duties. However, only the human being can transform the rest of creation. In this dynamic and evolutionary interrelationship, the precautionary principle should guide human actions: not everything that can be done (science) must be done (ethics).

In an unprecedented way, more than 200 scientific journals simultaneously have published an article signed by directors of publishing groups and medical institutions from around the world1. The text warned about the advent of a global health crisis, as a result of climate change and the reduction of biodiversity. It pointed out that both are the result of the imbalance produced by irresponsible human actions. The tragedy is that this intervention by man is not only harmful to other living beings but can be suicidal for our own species.

Health problems will result from a lack of clean water, food, and habitat, along with extreme weather events, air pollution, garbage accumulation, and increased infectious diseases, including pandemics. Thousands of species and millions of living beings have been disappearing at an accelerated rate in recent decades. Biodiversity has never fallen so much. If we do not intervene, it will be the sixth wave of mass extinction of life on Earth, although, unlike the previous ones, the responsibility for this one lies with human action2.

The experts’ brief concluded with a series of recommendations to reverse the problem. It is necessary to explore alternative visions of what a good quality of life means (i.e., one that is not dependent on consumerism), to rethink the consumption of natural goods (discarded and recycled), to value inter-human relations (confronting individualism), to reduce social inequalities, and to promote education in values. All this will result in better physical and mental health of human beings in the 21st century1.

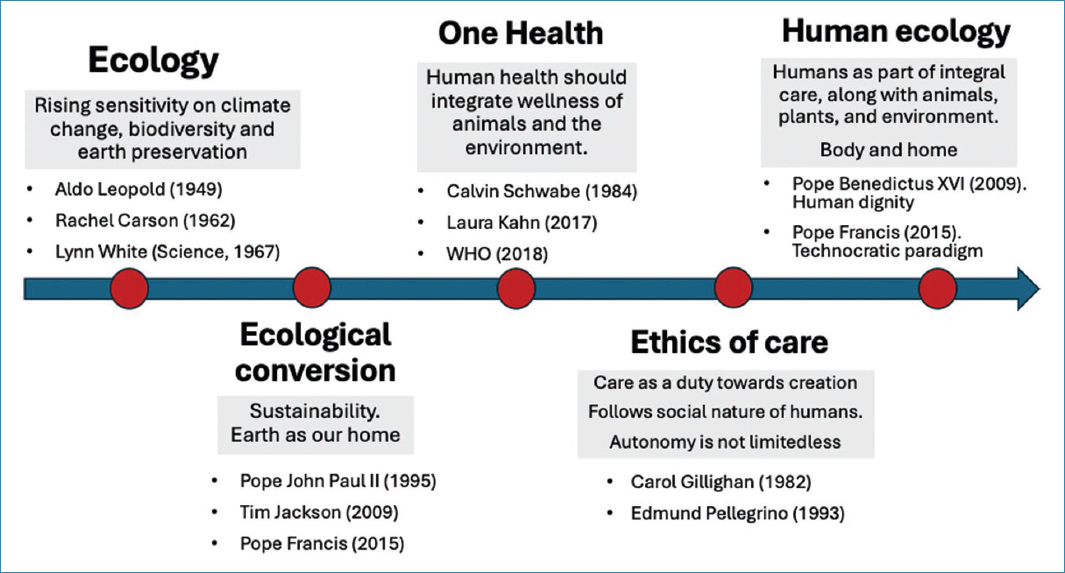

A call to caring for the world: ecological conversion

In the history of the last century, we can identify three major texts that have been a catalyst for awareness of caring for the planet (Fig. 1). First, and shortly after the end of the Second World War, Aldo Leopold published his book on the ethics of the Earth (A Sand County Almanac, 1949)3. It awakened sensitivity for the care of our planet. Nature should not be understood only as a means for human beings to obtain resources. It cannot be instrumentalized. Leopold says that the environmental crisis is rooted in an economistic reductionism. He underscored that humans are part of creation and must respect it; using is opposed to exploiting. In the face of anthropocentrism, biocentrism was awakened.

Figure 1. The evolving path in human ecology.

Rachel Carson is considered a key figure in the modern environmental movement and in the defense of ecosystems against inconsiderate human action. She was an American marine biologist, author of the book “Silent Spring” (1962)4, in which she denounced the harmful effects of pesticides (DDT) on the environment, especially on birds. In a posthumous book, “The Sense of Wonder” (1965)5, she argues that to defend nature, one must experience its greatness. This fascination fosters a deeper awareness and responsibility for the environment.

In 1967, Lynn White published a disruptive article in Science6, where he examined the possible determinants of the abuse that human beings were making of the rest of living beings and resources on the planet. White painted a scenario where the culture of Judeo-Christian roots would have led to extreme anthropocentrism, with a misinterpretation of the biblical command in Genesis to “increase and multiply; and rule the world.”

In the face of these positions, in recent years, the Catholic Church has spoken out on environmentalism and the care of the common home. Pope St. John Paul II7 stressed the need for an ecological conversion, where man recognizes himself as a minister of the creator. Ecology is of interest insofar as it refers to the way in which man relates to the natural and social environment in which he lives and for which he is responsible. There is no room for the abuse of nature and its exploitation, disregarding the rest of the human community and nature.

Tim Jackson is a British economist and sustainability expert who, in 2009, defended the concept of ecological conversion, understood as a shift in the way societies, economies, and individuals relate to the environment. It is not only about adopting green technologies but also involves a deep transformation in values, behavior, and policies that prioritize ecological sustainability over relentless economic growth. For Jackson, ecological conversion is essential for creating a society where prosperity is not defined by material consumption but by the quality of life and the well-being of both people and the planet8.

Finally, Pope Francis in the encyclical “Laudato si” (2015)9 has written important reflections on the care due to our common home. This reference text underlines the duty to protect God’s work as an essential part of a virtuous existence. Creation, the work of God, has an intrinsic (objective) value, which goes beyond its instrumental character for human beings. Francis would say that everything is connected, so that care for nature reflects the moral conduct of the person. In this way, ecology and care for other human beings, especially the most vulnerable, and the fight against poverty are the same aptitude of the human being.

One Health

The American epidemiologist Calvin Schwabe is credited with using the term “one health” for the first time in 1976, referring to the close interrelationship between human and animal health10. In 2004, the Rockefeller University organized a conference under the title “One World – One Health,” which concluded with the “Twelve Manhattan Principles,” which pioneered new terminology to implement global health.

Laura Kahn is a US physician who has emphasized the importance of a holistic approach to new health challenges. She advocates for integrated research and policy that involves veterinarians, physicians, and environmental scientists, working together to address issues such as zoonotic diseases, environmental degradation, and antibiotic resistance11.

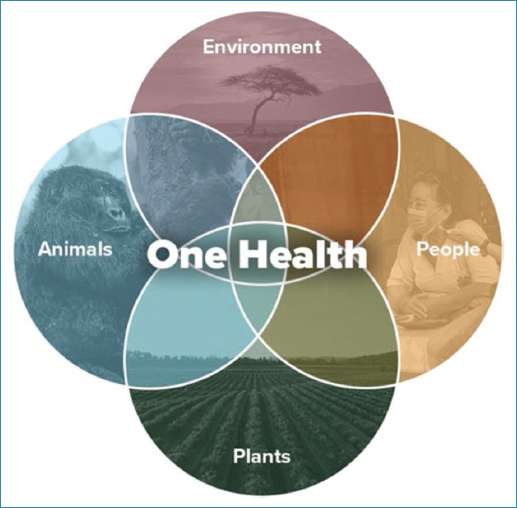

In 2018, four international organizations (World Health Organization [WHO], Food and Agriculture Organization, UN, and OIE) signed a collaboration and joint promotion agreement for “One Health,” highlighting the close relationship and interdependence between human, animal, and environmental health. It is a comprehensive and unifying approach to balancing and optimizing the health of people, animals, and ecosystems. It enables the full spectrum of disease control to be addressed, from prevention to diagnosis, management, and treatment, contributing to global health security.

However, it has been the unprecedented succession of pandemics of the XXI century (SARS, Ebola, avian and swine flu, Dengue, Chikungunya, Zika, Monkeypox, and above all, COVID-19) that have raised awareness on global health. Almost all these illnesses are zoonoses, that is, they come from an animal reservoir and/or there is a vector involved12.

According to the WHO, the One Health concept refers to the global objective of increasing interdisciplinary collaboration (public health, medicine, health, veterinary, research, environmental sciences, etc.,) in the health care of people, animals, and the environment, to be able to develop and implement programs, policies, and laws in favor of improving global health13. The UNs 2030 agenda addresses the wellbeing of humans, living beings, and ecosystems through 17 sustainable development goals. A framework for integrating one health in the 2030 agenda has been discussed extensively14.

The relationship between humans, other living beings, and ecosystems is dynamic (Fig. 2). With a holistic vision, “One Health” seeks to adapt to changing relationships that are currently particularly significant due to phenomena such as globalization, human travel and migration, changes in the geographical distribution of different animal species, climate change, deforestation15, intensive livestock farming, new animal migration routes, and environmental pollution. All these phenomena have favored the transmission of diseases, with jumps of microbes from animals to people (zoonoses), as new opportunities for close contact between humans and animals have arisen, in altered ecosystems12.

Figure 2. The elements of one health.

According to the World Organization for Animal Health, 60% of known human infectious diseases and more than 75% of emerging diseases are of animal origin (domestic or wild animals). Animal health is therefore essential for the maintenance of public health. This integration of the health of humans, animals, and ecosystems has to be reflected in the new policies of all countries16. The areas in which the One Health approach is particularly needed today are food safety, control of zoonoses, and the fight against antimicrobial resistance17.

Integral ecology

Ecology refers to man’s relationship with the environment and its care. Pope Benedict XVI was the first to draw attention to the relevance of human ecology as an integral part of Christian life18. Both the external environment (other living beings and environmental nature) and the internal environment (the person himself) need to be taken into account. The house we live in is an extension of the house we are. In this way, taking care of ourselves is true ecology to the extent that we take care of others and the environment. We are not loose pieces, which reach their fullness with self-care. On the contrary, humanity requires care for the environment to achieve its end. Man reaches his fullness in the interaction with other humans and with created things. Ratzinger says “the book of nature is one and indivisible: it incorporates not only the environment but also life, sexuality, marriage, social relations, in a word, integral human development.” Man must be seen as part of nature, created and willed by God. In a memorable address to the German parliament in 2011, Benedict XVI noted that “the respect that creation deserves includes man himself, the creature made in his image and likeness19.”

We must protect the vitality–life–of ecosystems and of human beings. Biology and anthropology must go in unison, saving each other. A throwaway culture, where there are second-class individuals for whom there is abortion, euthanasia, etc., is not typical of a society committed to human ecology. In the same way, the Pope noted that the instrumentalist abuse of environmental resources produces a new patient: the planet Earth.

The consideration of the human being as an immaterial or amorphous entity is the result of not accepting that we are soul and body. Pope Francis points to those who defend the motto “I am what I feel and/or desire,” considering their own body and environment as possible targets for technological interventions. This technocratic paradigm, which places extreme trust in technology, can damage and abolish the nature of the human being9.

In his book “The Abolition of man” (1943), C. S. Lewis caricatured a future time where human beings manipulate their species in such a way that they reach a point where they no longer recognize themselves. In the quest to overcome our limitations (illness, pain, frailty in the elderly, death, etc.), in the end, who would win? Of course, it would not be the human being himself20.

More recently, human ecology has been defined as the care of body and home21. A concern for the environment that does not include respect for human beings is not true ecology. Human dignity is destroyed when we want to reinvent the human being from our desire, instead of accepting our nature as a gift. In other words, we are born, not made. You have to listen to the language of nature. We must rediscover its value, not infrequently hidden.

Although the interest in human ecology by doctors would look recent, the link between medical ethics and ecology is clear. This topic has been extensively addressed by Edmund Pellegrino, one of the fathers of modern medical ethics. In his book “Helping and healing: a medical perspective” (1993)22, he discussed the virtues that drive doctors to achieve both their professional and human aspirations.

In summary, the new human ecology can be approached from the contemplation of four scenarios: (1) creation, considering that we are dependent and loved creatures; (2) human nature, which has been given to us and we are called to bring to its fullness; (3) the environmental and community environment, which we must take care of; and (4) the planet, as a common home.

The risk of unlimited autonomy

Ecological thinking underlines the value of life and the question of the place of the human being in the Cosmos. The human ecological vision helps us to overcome the hegemony of autonomy because it highlights the relationship of the human being with the environment and the impact that self-determination has on others and on the environment.

Although autonomy was initially proclaimed as a principle of bioethics to protect against abuse23, making one’s own decisions prevail over the wishes of others, it is not an absolute good. Autonomy is the starting point, not the destination. Own decisions that are harmful to others cannot be justified by the reason of autonomy. Autonomy taken to the extreme entails a rupture of interpersonal ties. Moreover, the absence of relationships is a form of abandonment and goes against due care.

In the name of autonomy, laws on abortion, euthanasia, etc., have been approved in some places where health care workers are pushed to participate in such practices against their wishes and beliefs. This violation of the principle of conscientious objection24 goes against human ecology.

The ethics of care

The creation described in Genesis gives an account of the beginning of the world and of the human being. But creation is a continuous act, which requires conservation. Care is the providence of the human being worldwide. In this regard, the essential nature of the human being’s relationship is exercised with the environment, other living beings, and other citizens.

Carol Gilligan was an American psychologist and feminist, known for developing the ethics of care. Her reflections on patient care have helped to give identity to the nursing profession. Her best-known book is “In a Different Voice” (1982)25, in which she defended that justice and impartiality not only guide the morality of men but also that of women, although women tend to prioritize interpersonal relationships and care for others.

The ethics of care that Gilligan proposed emphasizes the importance of empathy, responsibility, and mutual care in human interactions, rather than the application of universal and normative rules. It underlines the importance of interpersonal relationships and care in the ethical construction of society.

Care is a duty we have toward creation, of which the human being is the most important. It is an attitude that moves us to care, to let ourselves be cared for, and to take care of ourselves. Care and sustainability go hand in hand and support each other. Human care is a way of being close, with generosity and dedication, personal and collective, giving the other the value they deserve. Care is a way of understanding the world and acting accordingly; in this sense, it is a moral conduct. In the following sections, we will discuss a few topics in which considering the ethics of care in a context of human ecology could help reorient policies in the best of human dignity.

Human ecology and the case of germline gene editing

A group of Oxford philosophers, led by Julian Savulescu, has recently published a provocative article in Nature26. It argues that new genomic technologies (e.g., CRISPR/Cas9) should be used to prevent babies from being born with genes that predispose them to an increased risk of diseases. Some conditions are very common, such as coronary heart disease, schizophrenia, diabetes, major depression, or Alzheimer’s. As they are polygenic, gene editing of multiple genes would have to be used at the same time.

In response to such a view, geneticists have stressed that gene editing in human embryos is an experimental technology27. We know that its use has undesirable effects, some known and others unknown at the moment. It is far from certain. Therefore, it is not ethically possible to justify the manipulation of the human embryo (with the risk of its destruction) by arguing that it is desired to prevent diseases in adults.

Other problems regarding the use of gene editing in human embryos include the lack of equity in access (expensive technology), privacy (knowledge to third parties), irreparable harm to offspring, and possible abuse for improvement (transhumanism), without the aim of curing28.

Medical ethics – and therefore human ecology – is in favor of promoting research into medication to treat genetic diseases early in fetuses of pregnant mothers. The possibility of diagnosing fetal diseases in blood samples from the mother is already a reality, as recently pointed out with the case of a fetus with spinal muscular atrophy successfully managed treating the pregnant mother with risdiplam29. On the contrary, it is necessary to regulate the use of gene editing to avoid abuses in the manipulation of human embryos, especially when obtained by in vitro fertilization. A group of experts, including several Nobel laureates, has made an urgent call for a moratorium on the use of gene editing in human embryos, until more reliable information on the associated risks30.

Human ecology in the face of current sexually transmitted infections (STI) rebound

The WHO defines health as a “state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being31.” Hence, it refers to a broader conception of human being, where both physical and psychological aspects are taken into account. This definition is more aligned with what is now understood as human flourishing32–34. There is no doubt that sexuality is a dimension of human being for which flourishing could be a good approach to deal with. Developments in this sense are similarly related to human ecology, as noted above, since it pursues the care of human beings as a special part of nature35.

STIs are rising unprecedently after the COVID-19 pandemic. They have become the second in the global rating of infectious diseases after respiratory infections36. Globally, over 1 million new STIs are diagnosed every day. Although four conditions are the most representative and of obligatory declaration (gonorrhea, syphilis, chlamydia, and human immunodeficiency virus), there are many other prevalent STIs, including trichomonas, herpes simplex, papillomavirus, and viral hepatitis. Overall, STIs determine important sexual, reproductive, and maternal – child health consequences.

There have been important advances in STI diagnosis and screening tests, as well as in treatment strategies, including prophylaxis. However, STIs continue to rise in an unprecedented way globally36, proving that current strategies are failing. Many experts consider that education and information to citizens needs to be reformulated with interventions aimed to build a healthier society, as has been undertaken with tobacco, alcohol, diet, and exercise. Indeed, lifestyle changes have the potential to reduce mortality by 43% whereas medical care improvements may contribute with only 11%. However, in countries such as the United States, only 1.5% of resources are invested in modifying lifestyle habits, being 90% used in providing medical services37. Are we making us accomplices rather than confronting the problem’s root?

To promote well-being or “flourishing,” the education of adolescents and young adults should be well aligned with human ecology, being the meaning of sex embraced within the respect for others and human love38. Therefore, new approaches in sexual health that represent a clear benefit for individual persons and society should be assessed. In this way, respecting individual’s freedom, favoring a cultural evolution tended to delay the age of first sexual intercourses39,40 and the avoidance of multiple sex partners would benefit the whole society.

Human ecology and the surge of gender dysphoria

Around 1-2% of the population displays genitalia and/or sexual behaviors that do not fit well within the classical male or female stereotypes. The distinction between sex and sexuality derives from considering biology and psychological/social determinants, respectively. Whereas binarism is clear for sex (XX or XY), acknowledging the exception of differences/disorders of sexual development (DSD), formerly intersexual states, the spectrum of sexuality is wider and somewhat bimodal. Sexuality refers to behaviors such as sexual orientation/attraction and self-identity. When they are not aligned with sex (biology), we acknowledge them as homosexuality or gender dysphoria, respectively.

DSD are congenital conditions involving atypical development of chromosomal, gonadal, or anatomical sex41,42. It is important to differentiate these conditions, formerly known as intersexual states43,44, from other disorders of the sexual sphere that largely result from acquired (cultural) determinants rather than a biological basis. This is generally the case for homosexual and transgender behaviors. Accordingly, the largest genomic study conducted so far over nearly half a million persons did not find a gay gene45. In other words, distinction should prevail for “nature” versus “nurture” when considering disorders of the sexual sphere.

The International Classification of Diseases, Eleventh Edition46 considers many of the atypical sexual behaviors within a category of compulsive disorders with hypersexuality that may interfere with regular, ordinary life, job performance, and social relationships. On the other hand, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition47 includes sexual dysfunctions, gender dysphoria, and paraphilias among the list of mental disorders.

The term “differences” instead of “disorders” has been proposed for DSD, since it is more neutral and inclusive. It would emphasize diversity rather than illness. However, the back side of this willingness to avoid any possible stigma or discrimination is that medical research and funding, as well as development of treatments, are mainly encouraged when conditions are considered as pathologies, since only then can interventions aimed to ameliorate or cure them be pursued. On the contrary, if such conditions are interpreted as part of the normal spectrum, acceptance would be the most convenient approach, avoiding the chance of attempting modifications.

Sex and sexuality are fundamental parts of the person and required for achieving human wholeness and flourishing48. Sexual disorders and behaviors that distort this critical role deserve to be addressed by us, physicians, for our patients’ good49. Whereas we should respect anyone with atypical sexual phenotypes and/or behaviors, providing help for ameliorating suffering from these conditions is warranted. In fact, there is a moral imperative to do so49. Otherwise, advances in scientific knowledge would not translate into improvements in human health for this subset of persons.

Understanding in this way, the meaning of sex and its binary nature provides an additional benefit, which is the opportunity to bring back individuals who, at any time later, would reconsider their sexual behavior. As Barbara Golder recently pointed out in an editorial, “these persons are called to fulfill God’s will in their lives,” like anyone, and try to overcome “the difficulties they may encounter from their condition50.”

Conclusion

Rising awareness of biodiversity and ecosystems since the 60 s has evolved to include human beings. In this ecological conversion, our duties to animals, plants, and the environment should be aligned with attention to our own species. Ecology has become human ecology, whereas health has become one health. This integral ecology should inspire human actions, developing a framework of ethics of care in a pyramidal way, attending consecutively men, animals, plants, and the planet we live in. Whereas autonomy must be respected, it is not absolute. Rather than empowering us with no limits, we should view all creatures on earth as a gift and ourselves as caregivers. The cautionary principle should guide research and technological advances. We deeply believe that understanding human ecology in this way will push the achievement of the 2030 UNs agenda.

Funding

None.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical considerations

Protection of humans and animals. The authors declare that no experiments involving humans or animals were conducted for this research.

Confidentiality, informed consent, and ethical approval. The study does not involve patient personal data nor requires ethical approval. The SAGER guidelines do not apply.

Declaration on the use of artificial intelligence. The authors declare that no generative artificial intelligence was used in the writing of this manuscript.

References

1. Abbasi K, Ali P, Barbour V, Benfield T, Bibbins-Domingo K, Hancocks S, et al. Time to treat the climate and nature crisis as one indivisible global health emergency. JAMA. 2023;330:1958-60.

2. Anonymous. Seize the moment:researchers have a rare opportunity to make progress in protecting global biodiversity. Nature. 2023;622:7-8.

3. Leopold A. A Sound County Almanac. New York:Oxford University Press;1949.

4. Carson R. Silent Spring. New York:Houghton;1962

5. Carson R. The Sense of Wonder. New York:HarperCollins;1965.

6. White L Jr. The historical roots of our ecologic crisis. Science. 1967;155:1203-7.

7. Pope Jean Paul II. Evangelium Vitae. Vatican:Vatican Press;1995.

8. Jackson T. Prosperity Without Growth:Economics for a Finite Planet. London:Earthscan;2009.

9. Pope Francis. Laudato si. Vatican:Vatican Press;2005.

10. Schwabe C. Veterinary Medicine and Human Health. New York:Williams and Wilkins;1976.

11. Kahn L. Antimicrobial resistance:a one health perspective. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2017;111:255-60.

12. Morens D, Fauci A. Emerging pandemic diseases:how we got to COVID-19. Cell. 2020;182:1077-92.

13. World Health Organization. One Health. Available from:https://www.who.int/health-topics/one-health#tab=tab_1

14. Queenan K, Garnier J, Rosembaum-Nielsen L, Buttigieg S, de Meneghi D, Holmberg M, et al. Roadmap to a one health agenda 2030. CABI Rev. 2017;12:1-18.

15. Chuvieco E, Pettinari M, Koutsias N, Forkel M, Hantson S, Turco M. Human and climate drivers of global biomass burning variability. Sci Total Environ. 2021;779:146361.

16. Behera MR, Behera D, Satpathy SK. Planetary health and the role of community health workers. J Family Med Prim Care. 2020;9:3183-8.

17. Soriano V. “One Health”:toward an integral ecology of health. AIDS Rev. 2024;25:179-81.

18. Pope Benedictus XVI. Caritas in Veritate. Vatican:Vatican Press;2009.

19. Pope Benedictus XVI. Speech to the German Parliament. Berlin, 2011. Available from:https://www.vatican.va/content/benedictxvi/es/speeches/2011/september/documents/hf_ben-xvi_spe_20110922_reichstagberlin.html

20. Lewis CS. The Abolition of Man. New York:McMillan Ltd.;1943.

21. McCarthy MC. Human ecology:body and home. Humanum. 2016;4:1-3.

22. Pellegrino ED, Thomasma D. Helping and Healing:A Medical Perspective. Washington, DC:Georgetown Medical Press;1993.

23. Beauchamp T, Childress J. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. Nueva York:Oxford Medical Press;2019.

24. Soriano V, Montero B. Current challenges for conscientious objection by physicians in Spain. Linacre Q. 2024;91:29-38.

25. Gillighan C. In a Different Voice. Boston:Harvard University Press;1982.

26. Visscher P, Gyngell C, Yengo L, Savulescu J. Heritable polygenic editing:the next frontier in genomic medicine?Nature. 2025;637:637-45.

27. Carmi S, Greely H, Mitchell K. Human embryo editing against disease is unsafe and unproven – despite rosy predictions. Nature. 2025;637:554-6.

28. Soriano V. Jérôme Lejeune passed away 25 years ago. Hereditas. 2019;156:18-20.

29. Finkel RS, Hughes SH, Parker J, Civitello M, Lavado A, Mefford HC, et al. Risdiplam for prenatal therapy of spinal muscular atrophy. N Engl J Med. 2025;392:1138-40.

30. Lander ES, Baylis F, Zhang F, Charpentier E, Berg P, Bourgain C, et al. Adopt a moratorium on heritable genome editing. Nature. 2019;567:165-8.

31. World Health Association. Preamble to the Constitution of the World Health Organization. International Health Conference. New York:World Health Association;1948.

32. VanderWeele T. On the promotion of human flourishing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114:8148-56.

33. Seligman M. Flourish:A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-being. New York:Free Press;2011.

34. Keyes C. Promoting and protecting mental health as flourishing:a complementary strategy for improving national mental health. Am Psychol. 2007;62:95-108.

35. Trudel-Fitzgerald C, Millstein R, von Hippel C, Howe C, Tomasso L, Wagner G, et al. Psychological well-being as part of the public health debate?Insight into dimensions, interventions, and policy. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:1712.

36. Soriano V, Blasco-Fontecilla H, Gallego L, Fernández-Montero JV, de Mendoza C, Barreiro P. Rebound in sexually transmitted infections after the COVID-19 pandemic. AIDS Rev. 2023;26:127-35.

37. Dever G. An epidemiological model for health policy analysis. Soc Indic Res Int Interdiscip J Qual Life Meas. 1976;2:453-66.

38. Chen Y, Hinton C, VanderWeele T. School types in adolescence and subsequent health and well-being in young adulthood:an outcome-wide analysis. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0258723.

39. Osorio A, López del Burgo C, Carlos S, de Irala J. The sooner, the worse?Association between earlier age of sexual initiation and worse adolescent health and well-being outcomes. Front Psychol. 2017;8:1298.

40. Calatrava M, Beltramo C, Osorio A, Rodríguez-González M, De Irala J, Lopez del Burgo C. Religiosity and sexual initiation among hispanic adolescents:the role of sexual attitudes. Front Psychol. 2021;12:715032.

41. Lee P, Houk C, Ahmed S, Hughes I. Consensus statement on management of intersex disorders. International consensus conference on intersex. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e488-500.

42. Weidler E, Ochoa B, van Leeuwen K. Prenatal and postnatal evaluation of differences of sex development:a user's guide for clinicians and families. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2024;36:547-553.

43. Aaranson I, Aaranson A. How should we classify intersex disorders?J Pediatr Urol. 2010;6:443-6.

44. Adam MP, Fechner PY, Ramsdell LA, Badaru A, Grady RE, Pagon RA, et al. Ambiguous genitalia:what prenatal genetic testing is practical?Am J Med Genet A. 2012;158A:1337-43.

45. Ganna A, Verweij KJ, Nivard MG, Maier R, Wedow R, Busch A, et al. Large-scale GWAS reveals insights into the genetic architecture of same-sex sexual behavior. Science. 2019;365:eaat7693.

46. ICD-11. Available from:https://icd.who.int/en

47. American Psychiatric Association. DSM-5-TR. Washington, DC:American Psychiatric Association;2022

48. VanderWeele T. A Theology of Health. Notre Dame, Indiana, USA:Notre Dame Press;2024.

49. Pellegrino E, Thomasma D. For the Patient's Good. New York:Oxford University Press;1988.

50. Golder B. Challenges, conflicts, and opportunities. Linacre Q. 2024;91:341-4.